Tina Stephenson-Chin

Previous Executive Director of Pedagogy, Tina oversees Reggio Emilia (Asia) and a range of professional development initiatives. Tina has been an active contributor to popular and academic publications, in Canada and Asia, on a range of behavioral and education issues for the past 10 years. She was previously Senior Lecturer for Middlesex University London and Open University Hong Kong in teacher qualification granting programmes including their Honours B.A. in Early Childhood Studies – the only bachelor’s degree in education from a foreign institution fully-accredited in Hong Kong. She is also a member of the Ontario College of Teachers in Canada and The National College of Teaching and Leadership in the U.K.

I enjoy listening to my son talk and the way he expresses himself - he has always been marvelous to hear. Starting in his earliest months, we listened with attentive joy to all the sounds he made, picking up on his communication and filling in gaps for him as his sounds developed into words. Then, his words came together to express ideas, and now at four years old, his ideas have grown into opinions and conversations. However, language development is not an enjoyable topic for all of us.

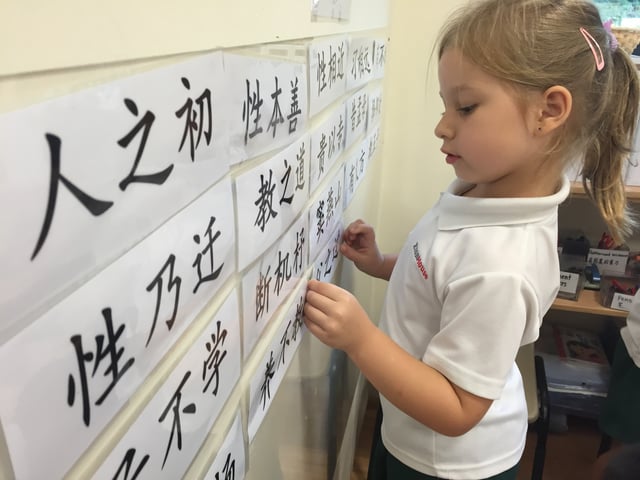

We live in a world where multiple languages are part of everyday communication, and speaking the right language or combination of languages can give our children a serious advantage. Many parents are uncertain about which language to raise their child in and how best to go about language learning for their child. Raising a bilingual child is a surprisingly contentious topic and seemingly full of conflicting information. This is partially to blame on the fact that language acquisition is big business with language courses and programmes being an important revenue source in the field of education.

Here are three principles, followed by experts, which can help you make the best choices in raising a bilingual child:

Principle 1: Language is a need, not a hobby

Perhaps you want your child to speak English to improve their future education options, or maybe they speak English at home and you want them to learn to speak another language to benefit them in the future. Whatever languages you choose or your reasons for choosing them, the first and most important thing we all must remember about language acquisition is that language is primarily used to communicate with the people we love and live with - which, in most cases, is our family.

We learn to speak so that we can communicate with the people we love and our loved ones are the ones we are hardwired to communicate with. This is why children learn their first language (mother tongue) from their parents. Although many parents want to have their children learn language for reasons associated with their future, our first (and occasionally second) language is an immediate need, not a strategic advantage. We need to give our children the communication tools they require to play, build trust, learn about loving relationships. They are much more likely to be successful in all these important early experiences if the language they learn in comes directly from the people they love the most.

Principle 2: One person, one language

I am a strong believer of the tried and true methods of language acquisition, and one of the best established rules is this:

The best way to achieve fluency in a language is to learn one language from one person, ideally our parents, without switching languages frequently.

The most successfully bilingual children are raised in families in which one parent speaks one language and another parent speaks a different language. That is bilingual best practice and most experts would argue that one person one language, in dual language environments is the only way to raise a bilingual child without risking serious expressive and receptive language delays.

A parent who is frequently switching languages in an attempt to make a child bilingual is, in my experience, placing that child at risk of language delay. In my decades of work in early childhood, I have occasionally seen children who have become bilingual from code switching, but I have much more commonly seen children become language delayed because of experiencing too many intermixed languages at home.

There is much debate about frequently switching languages, also known as code switching, when you speak to your child. But in my opinion, achieving fluency in a single language is important to building a strong foundation of language and too much code switching erodes the language foundation.

Children raised in a dual language environment with one parent using only one language are often slower in acquiring language than their monolingual peers. However, it does seem that they catch up within a developmental range of about 8 months.

However, children from code switching environments can experience as much as 2 years difference in language acquisition and can only catch up with their peers after their parents simplify the language environment at home.

Principle 3: Quality in, quality out

I speak English and a small amount of a few other languages. My second languages allow me to follow most of a conversation, but not to form complex arguments. My husband is similar although his Cantonese and Mandarin are much better than mine - he is not truly fluent in any language other than English. This is why we have opted to raise our son in English only. Our son is learning from every word we say and it is vitally important that he gets quality input. If my pronunciation is shaky, my vocabulary inaccurate and my sentence structure inconsistent, my son will pick up these habits from me and those habits will be very difficult if not impossible to correct later on.

The ultimate idea in learning is that good quality input creates better quality output, which is why it is vitally important that I talk to my son in my own mother tongue no matter what it is. He needs me at my linguistic best to give him the best possible language learning opportunities I can give. We always want to give our children the best we can offer and when it comes to language learning this simple truth continues to apply - give them the best of yourself.

Visit EtonHouse and learn more about our bilingual inquiry-based curriculum.

-1.png)