-1.png)

EtonHouse Singapore

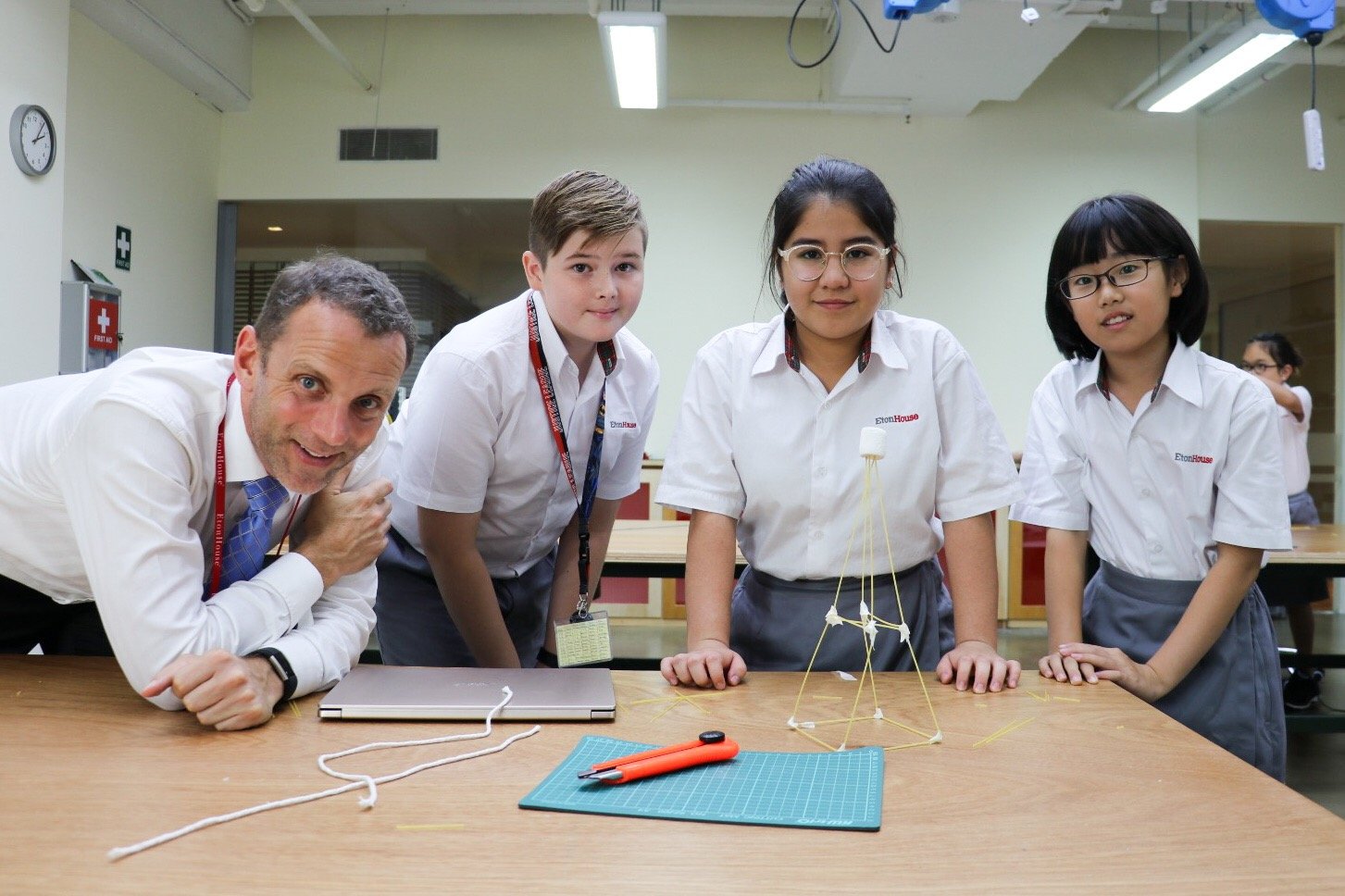

In the maker space at EtonHouse Orchard International School, students huddle over a table in groups of three to four. They talk excitedly about weight and support, fiddling with dry spaghetti sticks and one fluffy marshmallow. There’s laughter and cheering. What’s going on?

Welcome to the Spaghetti Marshmallow Challenge, an activity for beginners in design thinking so participants learn about prototyping and testing.

In 20 minutes, construct the tallest tower possible with the marshmallow at its peak. Each group has the use of 20 sticks of spaghetti, one marshmallow, 1 yard (91cm) of tape, and 1 yard of string.

EtonHouse Orchard Principal Alec Jiggins tells us why he runs this challenge in his school — for children and adults.

What is the purpose of this exercise?

The Spaghetti Marshmallow Challenge is conducted for students to get them to question their own way of thinking and focus on possibilities instead of fixating on getting the right answer.

A lot of the time, we are told that wrong is bad. But getting the wrong answer is just feedback because it would eventually lead to the right answer. Hence, the idea is to free students from the fear of making mistakes so they are not denied the opportunity of achieving their goals.

What can be learned from the Spaghetti Marshmallow Challenge?

People should learn that education can be fun! Through the challenge, students are taught the importance of teamwork and working together. It is also through genuine collaboration, that there will be better ideas.

People also learn that prototyping matters because when you prototype and test, you come up with different ideas instead of just sticking to one solution, which carries high stakes.

The learning that takes place during the challenge is also deep. The students also learn that failure is not final, and they should be willing to try and fail then try again.

What have you observed running this challenge?

I have facilitated the Spaghetti Marshmallow Challenge for adults and children. It is interesting to witness how children often do better than adults.

I have also observed that the older and more educated the participants are, the higher the tendency for their thinking to be more linear. Whereas children tend to prototype and develop the structure along the way, testing as they go along. This is because the participants who are more educated tend to think that there is a right or wrong answer as opposed to what should and could be done.

Another observation is that when there are incentives, the overall height of all the structures becomes lower. Possibly because the greater urge to win makes teams more risk adverse and they prototype less, leading to less successful models.

How do we guide our children so they don’t become linear in their thinking?

It is through education! Teachers should ask open-ended, “what could” questions instead of “what should” questions. It is also important for education to evolve from just delivering content and compliance to instilling creativity and innovation through tinkering.

The marshmallow is the obstacle and it is analogous to what needs to be improved and what is imperfect in the project. In the case of education, the marshmallow is like the operations of a school — just because it works do not mean it cannot be improved. In the case of EtonHouse Orchard, we have broken down the IGCSE curriculum to three years instead of two, and made the learning more project-based, hence applying two prototypes into delivering the IGCSE curriculum.

You can find a guide to the Spaghetti Marshmallow Challenge here.

The activity shot to fame by way of a Ted Talk in 2010 by Tom Wujec, author and fellow at Autodesk, who found that out of the 70 or more challenges he has run for all sorts of people including top business executives, kindergarteners built the best structures.

“So there are a number of people who have a lot more ‘uh-oh’ moments than others, and among the worst are recent graduates of business school. They lie, they cheat, they get distracted, and they produce really lame structures,” says Wujec. “And of course there are teams that have a lot more ‘ta-dah’ structures, and, among the best, are recent graduates of kindergarten.”